George Oduor from CABI explains an new approach to sustainable change in legume technologies.

The goal of any long-term development project is to create sustainable changes in awareness, attitude and ultimately behaviour. In the first phase of the Africa Soil Health Consortium (ASHC) soil fertility projects, messages especially to farmers were developed in order to facilitate these changes. The ASHC team helped to develop print-ready materials that the organizations agreed to reproduce and distribute. N2Africa was one of the most active partners of ASHC during this phase.

Many institutions took up the offer of development support. However, in practice we had to deal with the frustration that our partners did not get the materials out into the field, and could not meet their part of the deal. Whilst this is disappointing, we hope that the training received will create a sustainable change in the way research institutions package technical information in more appropriate and farmer-friendly ways. A legacy of a web-based integrated soil fertility management (ISFM) library containing over 300 resources was also developed.

In the second phase of the ASHC project, CABI and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation corrected the structural flaw in the approach used in the first phase by ensuring stronger and more sustainable delivery. The core focus on integrated soil fertility management remained. Just like the assumption that farmers will find the best solutions (combination of selected improved seeds and varieties, application of organic matter and fertilizers, the use of legumes in rotation and the adoption of good agricultural practices) for their farms. However, the ways of working have changed significantly.

ASHC is now charged with forming, and working within, partnerships to ensure that soil fertility messages are disseminated, at scale, to smallholder farming families. In short:

- The new approach is based on a series of campaigns sharing the same technical information in different media;

- The messages in the different media are nuanced, so that they meet the information needs of different members of the small-scale farming households.

We are looking for evidence of what combinations of media, and in which circumstances, result in changes in attitude and behaviour in small-scale farming families. We are also interested in the impact that diffusing agricultural information through different family members will have on how decisions are made. Simply put; Will young people and women in farming families be empowered by accessing good quality farming information?

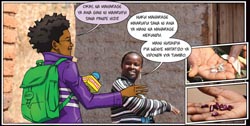

| In late 2015, we wanted to pilot the campaign approach. We first approached N2Africa, with whom we started working together on a pilot campaign promoting common bean technologies to small-scale farmers in northern Tanzania. Subsequently, Farm Radio International came on board to recruit a suitable radio station. Shujaaz (Well Told Story, see Podcaster 33) worked with us to develop two story lines in their comic and social media platform, showing how a young farmer and an agro-dealer were working with improved legume technologies. |

A picture from Shujaaz |

Our research partners were IITA and I-logix, a Nairobi-based firm. I-logix were asked to undertake a major telephone research pilot with over 3,000 farmers. This research was to identify how farmers felt about different legume technologies, especially those relating to market-ready inputs (improved seed varieties and fertilizer). At every stage of the campaign, Selian Agricultural Research Institute (SARI) and Wageningen University gave technical support.

A realistic danger in development communications is that some believe that information is the silver bullet and that better communications will lead to a permanent change in farming practice in Africa. This is not true. And as development communications professionals we need to assert that information is essential, but not sufficient to bring about sustainable change. The reasons farmers do apply new technologies vary. However, farmers are rational and they need to have access to both input and output markets to make investments viable.

The 2015 pilot was designed to help partners understanding the intricacies of running a campaign. What became clear through the early findings of the I-logix research was that there are significant numbers of farmer who are able to apply improved legume technologies, but that they are frustrated by inadequate supply chains for key inputs. And whilst overall there were indications of strong demand for inputs amongst some farmers, their geographically dispersal made it hard to serve them as a market. So, further work is needed to convert this latent demand into a sustainable input supply system.

During the pilot project in Tanzania, the extent of the problems with the legume technology inputs became clearer. Results of the farmers survey showed very strong farmer preference for improved seed varieties that are still not registered for use in Tanzania. Whilst an informal, unregulated economy is operating at scale to provide farmers with their preferred varieties of seed, projects like ours cannot be seen to be endorsing or circumventing the national systems. So, we cannot provide good agronomic advice to support the unregistered varieties. During the life of the project, we anticipate that pressure from the farmers will result in their preferred varieties being formally registered.

We found that stocks of registered improved seeds are in short supply. By the end of the season, as bean grain stocks reduce, the market price for seed is very close to the price of grain. This tempts many seed growers to sell seed stocks into the grain markets, exacerbating the shortfall in improved seed stocks for the following season.

We discovered that, to build sustainable markets, bean seed dealers wanted to advocate planting new bean seed every year. In reality, seed can be saved for several seasons. Annual seed replenishment from even a fraction of bean growers would soon wipe out the inadequate seed stocks. So, the Legume Alliance is suggesting production of new seed every three seasons. The logistical challenges of providing bean seed at scale are significant. The Legume Alliance now includes the Agricultural Seed Agency (ASA), which is working to bulk up more seed. In addition, the African Fertilizer Agri-business Partnership (AFAP) will pursue the policy issues associated with matching common bean seed supply and demand.

In 2015, inoculants of nitrogen fixing rhizobia strains were officially registered in Tanzania, with approval for a limited number of legumes. Common bean may well be added to the list, as effective strains of rhizobia are isolated and marketed. Commercially produced rhizobia inoculants are a highly cost-effective legume technology. However, it has a limited shelf life (6-12 months depending on the brand and packaging) and requires special handling on the part of the input supply chain and the farmers themselves. So, there is a lot of work required in building demand and putting in place effective supply chain that are fully informed to work with this new input. There is also work to be undertaken to fully share the benefits – not just on the seasons legume crop, but in terms of realistic claims that can be made about the nitrogen left behind for subsequent crops. This level of economic data helps farmers evaluate the benefits and costs of the different approaches and what they can consider as their best-bet ISFMmix.

In theory, fertilizer for use on legumes should be available. Particularly, P-fertilizers are designed to kickstart the legume into producing nitrogen. However, culturally beans are seen as a crop that needs no fertilizer. Consequently, the economics of fertilizer use in beans needs to be clearly spelt out. Input dealers appear to be reluctant to hold stocks of specialist fertilizers. The Legume Alliance is now looking how to build both demand and supply chains with the support of point of sale material and training in the agro-dealerships and mass extension.

There are real opportunities within the supply chains for improved legume technologies for information to be better integrated. This could include packaging and point of sale material designs that help farmers to correctly apply inputs. This could include simple steps like tape measure printed to help in spacing of seeds at planting and fertilizer application. Or providing clear guidance in each input package on how improved seed + organic matter and fertilizer + good agricultural practices can really boost crop production and replenish the soil.

Over the next four years the partners in the Legume Alliance will continue to review the obstacles to small-scale farming families adopting improved legume technologies. We will be piloting different approaches and including new partners to help us overcome barriers. The next article describes one of our future research activities, funded by SAIRLA.

The lessons emerging from these scale-up campaigns will be packaged and shared widely. So we have made a considerable investment in monitoring, evaluation and learning to know what is happening. This means we can advise others on how, and when, to create fully integrated campaigns and what works where. We look forward to sharing our findings here in the future. ASHC is in the process of setting up further partnerships in Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda.

George Oduor, CAB